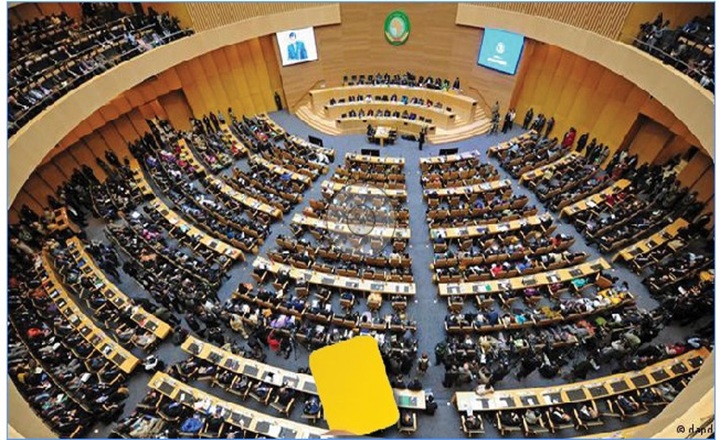

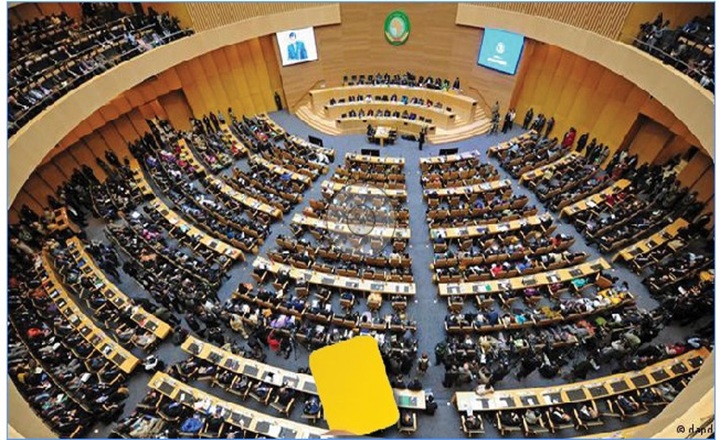

Yellow card to the African Union

The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was created on May 25, 1963, in Addis Ababa, in a historical context marked by the advent of African independence and the urgent need to protect these young sovereignties against neocolonialism, territorial fragmentation, and external interference. The OAU emerged as a political instrument for continental survival, at a time when African leaders understood that no newly independent state, in isolation, would have the capacity to confront an international system that was structurally unequal and hostile to the interests of the Global South. It was, above all, a defensive project, but also a gesture of historical affirmation: Africa refused to remain dispersed, vulnerable, and under tutelage.

Almost four decades later, on July 9, 2002, in Durban, South Africa, the African Union (AU) was officially born, following the Sirte Declaration of 1999 and the adoption of its Constitutive Act in 2000. The new organization presented itself as a conscious overcoming of the limitations of the OAU. It promised to abandon inertia, excessive reverence for the formal sovereignty of states, and silent tolerance of dictatorships, coups d'état, and massacres. The AU aimed to be more than a diplomatic forum: it wanted to be a central political actor, capable of intervening, preventing conflicts, promoting economic integration, defending democracy, human rights, and the strategic interests of the African continent in the international system.

This ambition did not arise from nothing. The OAU and the AU are direct descendants of Pan-Africanist thought. Kwame Nkrumah was its most radical and consistent theorist, stating that Africa should unite or perish, warning that political independence without economic, military, and cultural unity was an incomplete and fragile freedom. Léopold Sédar Senghor, albeit through a more cultural and humanist approach, advocated for an Africa conceived as a civilization, capable of engaging with the world without losing its soul. Patrice Lumumba embodied Pan-Africanism as a concrete revolutionary practice, denouncing the continuation of imperial domination under new guises and paying with his own life for this audacity. These leaders, among others, envisioned an Africa without artificial borders, with a commonly conceived education system, complementary economies, and a sovereign foreign policy. The African Union inherited this symbolic and historical legacy, and with it the responsibility not to betray it.

In legal and programmatic terms, the AU's Constitutive Act is ambitious. It speaks of economic and social integration, the promotion of democracy and good governance, peace, security and stability, the defense of African sovereignty and the dignity of the continent's peoples. It introduces the principle of non-indifference, formally breaking with the OAU's doctrine of absolute non-interference, and recognizes the organization's right to intervene in situations of genocide, crimes against humanity, and serious breaches of constitutional order. On paper, the AU presents itself as a modern organization, aware of African tragedies and ready to act.

In practice, however, more than two decades after its creation, an uncomfortable observation is inescapable: the African Union has failed to establish itself as a leading actor in the political and economic stabilization of the continent. Africa continues to be the scene of persistent armed conflicts, recurring coups d'état, protracted civil wars, and violently contested electoral processes. From the Sahel to the Horn of Africa, from the Great Lakes region to Central Africa, the AU almost always appears late, weak, or subordinated to external interests. Its peacekeeping missions are frequently poorly funded, poorly equipped, and politically conditioned. The organization proves incapable of imposing effective sanctions or deterring military and civilian elites who seize control of the state for private gain.

Even more serious is the systemic complicity of the African Union with weak, authoritarian, and corrupt governments. In the name of illusory stability, the organization has tolerated massive human rights violations, bloody repression against civilian populations, constitutional manipulations, and fraudulent elections. Election observation missions, which should be technical instruments for building democratic credibility, have in many cases become mechanisms for the political legitimization of regimes lacking popular legitimacy. Observers are appointed not for merit, independence, or ethical reputation, but for political calculations, affinities between elites, and exchanges of diplomatic favors.

Widely discussed cases in the African public sphere reveal the moral emptiness of these missions. Political figures associated with governments marked by economic collapse, accusations of corruption, and profound social unrest are chosen to lead sensitive electoral observation processes, compromising from the outset any semblance of impartiality. When these missions end in institutional instability or even military coups, the political responsibility of the African Union is relativized, diluted, or simply ignored, as if the organization were merely an innocent spectator of the African tragedy.

Meanwhile, the social reality of the continent remains devastating. Africa is a territory extremely rich in natural resources, but poor in social outcomes. Hunger, poverty, youth unemployment, forced migration, and a lack of prospects continue to define the lives of millions of Africans. The promise of real economic integration remains, to a large extent, rhetoric. The continent's strongest economies have not been effectively placed at the service of emerging economies. Internal trade barriers persist, integration infrastructure is insufficient, and value chains remain outward-oriented. The continent exports cheap raw materials and imports expensive manufactured goods, reproducing colonial logic under new guises.

The African Union's financial and political dependence on external partners further deepens this fragility. An organization that relies heavily on foreign funding to function can hardly assert itself as an uncompromising defender of African interests. This dependence conditions positions, silences criticism, imposes agendas, and undermines the continent's strategic autonomy. Thus, the AU often exists more as a form than as a force, more as a symbol than as an active historical subject.

This yellow card is not a call for the destruction of the African Union, but a stern warning. The idea of a united Africa remains valid, necessary, and urgent. What failed was not the pan-African dream, but its capture by political elites who transformed a continental organization into an instrument of self-preservation, complicity, and strategic silence. As long as the African Union continues to protect governments instead of peoples, presidents instead of citizens, apparent stability instead of structural justice, it will remain an institutional nullity in the face of the tragedies that plague the continent.

This yellow card will be recorded as a critical reminder, a tool for debate, and a historical wake-up call. Because Africa doesn't need more acronyms, empty summits, or ceremonial speeches. It needs political courage, moral consistency, and radical fidelity to the ideal that founded it.

Outras noticias

policy

Yellow card to the African Union

2026-01-15

Society

In Mulotane, a tractor is replacing public transport after roads became impassable due to rain

2026-01-15

Society

INCM strengthens mechanisms to block users who threaten national security

2026-01-15

policy

Mozambique showcases its enormous energy potential to investors in Abu Dhabi

2026-01-13

Society

Rosita Mabuiango, a symbol of resilience born from a tree during the floods of 2000, has passed away

2026-01-12

Copyright Jornal Preto e Branco All rights reserved . 2025