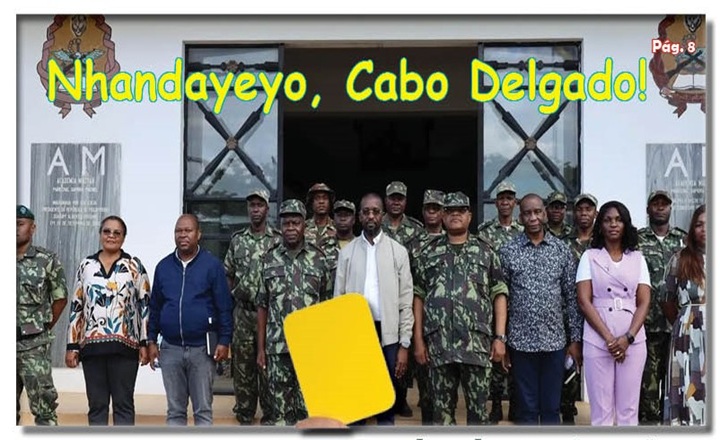

Yellow Card to the Ministry of Defense: When the Greed of the Few Sows Mourning Among the Poorest

Yellow card for the Ministry of Defense, not for the brave soldiers who fight without knowing the enemy, because sometimes both seem to obey the same command.

There are moments in a nation's life when the people are forced to raise their voices to avoid succumbing to lies, abuse, and greed. Silence, in these moments, ceases to be prudence and becomes complicity. This is the situation the Mozambican people find themselves in today, facing the shameful, almost subservient way the FRELIMO government has behaved towards Total Energies in the context of natural gas exploration in Cabo Delgado. This is a blunt warning, because the State has, in practice, become a secondary actor in its own territory, opening space for external interests to define national priorities, while the poor die, flee, and get lost in the dust and mud of endless displacements.

The government's submission to Total is not a result of naiveté; it is a result of convenience. It is the direct consequence of an elite that has become accustomed to treating the country as personal property, trading natural resources as if they were part of an inherited private patrimony, and not the collective wealth of a people who have never received the fruits of this treasure. This promiscuous relationship between the government and the oil company has become so evident that even the French justice system has managed to link Total to the instability in Cabo Delgado, while, within Mozambique, the same company is treated as a savior and untouchable, above any criticism, above the suffering of the population, above national sovereignty.

To understand the current absurdity, it is necessary to briefly go back to the genesis of the insurgency. Many attempts have been made to construct narratives that absolve the State: international terrorism, religious radicalization, external influences. All these explanations contain fragments of truth, but omit the essential. The insurgency germinated in fertile ground created by the Mozambican State itself: decades of neglect, structural poverty, historical inequality, destruction of expectations, and economic marginalization of the youth of Cabo Delgado. When the gas projects began, from Palma to Mocímboa, passing through Macomia and Nangade, the local populations were deceived with promises of employment, tranquility, and development. Instead, they were displaced, lost land, lost livelihoods, lost dignity. They saw the political elites become richer, while the local youth remained trapped in unemployment, frustration, and silent revolt. The State never wanted to discuss this origin because its own moral and political responsibility lies within it.

It was within this cauldron of tension, injustice, and opportunism that the insurgency found room to grow. Not because the young people of Cabo Delgado are terrorists by nature, but because they were pushed to despair by a country that never saw them as a priority. And when the insurgency erupted, the government used it not as a wake-up call to correct inequalities, but as an economic opportunity to reinforce mechanisms of control, patronage, and resource capture.

It is within this context that one of the most humiliating episodes in Mozambique's recent history unfolds: the hiring of the Rwandan Defence Force. It was never clear to the people whether the country had truly exhausted all internal alternatives. Whether our army was fully mobilized, whether internal resources were reorganized, whether veterans were called up, whether national military logistics were reinforced. None of this was explained. The government simply decided that Mozambique, as a whole, lacked the autonomous capacity to confront the insurgency. And, as if it were a failed state seeking a protector, it resorted to Rwanda, a military force whose presence in African conflicts has been systematically associated with economic interests, particularly in the mining and energy sectors. The question echoing throughout the country is direct: why Rwanda? Why ignore South Africa, its immediate neighbor, with greater military capacity, a historical presence in the region, and with whom Mozambique maintains long-standing cooperation agreements? Why specifically target a country that, coincidentally, maintains strategic relations with Total Energies and has a history of military action where multinationals benefit from instability?

The answer is harsh: because the Rwandan presence was not intended to protect Mozambique; it was intended to protect the Total project. And for that, the government did not hesitate to spend more than twenty million dollars that could have been used to equip our army, pay decent salaries, strengthen logistics, revitalize military bases, and restore the dignity of the Armed Forces. Instead, it preferred to pay foreign troops, in a clear gesture of strategic weakness and political submission.

While these decisions were made in the closed rooms of power, the comrades and their circles continued to enrich themselves. The clientelism within FRELIMO, long entrenched, has become a cancer that devours any attempt at socio-economic development. The exploitation of natural resources has become a restricted feast, accessible only to those with access cards to the party system. Security contracts, logistics contracts, supply contracts—everything has become a source of accelerated enrichment for a few, while the many, those who have nothing, continue to live in perpetual displacement, amidst hunger, fear, and uncertainty. For this elite, insurgency is not tragedy; it is opportunity. It is yet another pretext to hide shady deals, obstruct investigations, justify agreements, prolong power, and keep the people occupied with survival while the top of the pyramid collects dividends.

Total's connection to the instability in Cabo Delgado, acknowledged even by the French courts, should be enough for the Mozambican government to review its relations, demand transparency, impose conditions, and defend the people. But, on the contrary, the government maintains an almost feudal posture towards the oil company. Total speaks, the government agrees. Total suggests, the government executes. Total demands security for Afungi, the government shifts its military strategy and abandons entire villages to their fate. It's as if the country has been mortgaged and the government is content with the crumbs that slowly trickle into its coffers, crumbs that never improve the lives of the population, deadly crumbs, infested with blood, lack, and mourning, while the real fortunes disappear into private accounts, into hidden coffers, into the pockets of those who have learned to transform politics into a machine for accumulation.

And while the people of Cabo Delgado suffer, the government dances. There are always press conferences, fiery speeches about sovereignty, bilateral meetings with staged photographs, and empty promises about local development. But the stark truth is that the government is not concerned with the people; it is concerned with Total. It is concerned with the flow of gas. It is concerned with commissions, shady deals, and interests that operate behind the scenes. What is more precious in Cabo Delgado than its people? Nothing. But for the FRELIMO government, what is most precious is the organized plunder of resources.

Therefore, this yellow card is more than a warning: it is a moral cry. It is a denunciation that the State has lost its way. It is a warning that the people's patience has limits. If the government continues to act as a guardian of the interests of a foreign multinational, sacrificing Mozambican lives to protect others' profits, this yellow card will inevitably turn into a red card, and it will be raised not by intellectuals, journalists or critics, but by the people themselves, tired of being sacrificed in the name of the greed of a few.

Nhandayeyo, Cabo Delgado. We will not allow them to kill our brothers.

Genocide will not be part of our history.

Even if we have to die to live again!

Nhandayeyo Cabo Delgado!

Outras noticias

Society

19-year-old woman arrested for kidnapping newborns at Chókwe Rural Hospital

2026-01-08

Society

Tension in Salamanga: Conflict between the Community and Rangers of the Maputo Reserve

2026-01-08

policy

YELLOW CARD NO. 1 OF THE YEAR: BETWEEN PROMISES, POPULISM AND THE URGENCY OF NATIONAL PRIORITIES

2026-01-08

policy

YELLOW CARD FOR THE FIRST PRESIDENTIAL REPORT: NARRATIVE ARROGANCE, SYSTEMIC CONTINUITY, AND THE WASTE OF A FIRST YEAR OF HOPE

2025-12-25

Society

Intaka-Boquisso road floods after inauguration, leaving residents outraged

2025-12-25

Copyright Jornal Preto e Branco All rights reserved . 2025