Mozambique: the paradox of13th salaryof the poor people and the perks enjoyed by the rulers and their politicians

Paulo Vilanculo"

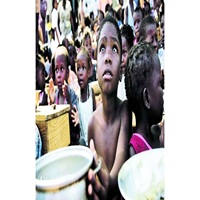

In Mozambique, the discourse on social justice and economic equity has been a constant unfulfilled promise. The distance between the average citizen's table and the politician's office is, today, a true reflection of a country where the people survive on meager wages, while the rulers wallow in privileges that defy reason. Between the austerity of the citizen and the luxury of the rulers, social justice remains just a postponed promise, and Mozambique thus reflects a cruel portrait of how inequality becomes institutionalized under the guise of legality.

In recent months, the National Union of Public Servants has accused the Government of intending to eliminate the payment of the 13th-month salary to state employees, a right enshrined for decades. Although the Executive has officially denied such an intention, the truth is that the new Regulation of the Career and Remuneration Subsystem for State Employees and Agents, approved by the Council of Ministers, contains an ambiguous clause. Article 32 recognizes the right to payment, but conditions it on "budgetary and financial availability," meaning that if there is no money, the State is exempt from the obligation. The paradox becomes clearer when one recalls that, in 2024, the Government committed to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to reduce the 13th-month salary to just one-third, maintaining the promise that in 2025 this payment would not exceed half. What kind of government is this that prefers to risk taking away, sacrificing its people, what little remains for their survival?

The sector-specific salary adjustments, in effect since April 2025, demonstrate the disproportionate nature of wage policies in the country. In salt mines and micro-enterprises, the minimum wage was set at 6,500 meticais; in agriculture and fishing, at 6,700; and in construction, at 8,400 meticais. The mining sector, considered the most profitable, guarantees 15,200 meticais per month. Converted to dollars, these amounts range from 102 to 237, sums that barely cover a family's basic needs. But the contrast is striking when one observes the income of those in power. A member of the Assembly of the Republic receives a monthly base salary of 174,249 meticais, plus representation and income allowances that bring the total to approximately 250,239 meticais, the equivalent of almost 4,000 dollars per month. In a year, each member of parliament accumulates more than 3 million meticais, which represents the income of twenty years of work for a salt worker.

The official narrative insists on “budget cuts,” “spending rationalization,” and “fiscal balance,” concepts that, in practice, seem applicable only to the working class. The State demands sacrifices from the people, but does not relinquish its own perks. In contrast, members of parliament accumulate millions in subsidies and benefits, while the working people live on wages that barely guarantee their daily bread. The distance between rulers and the ruled has become an ethical abyss. While citizens face unemployment, poverty, and the rising cost of living, the political class continues to benefit from perks, trips, subsidies, and unjustifiable privileges. In this scenario, many rulers seem to have completely distanced themselves from the social reality of the people they claim to represent. This picture of inequality is not only economic, but also moral and structural.

Despite official speeches invoking democracy and popular participation, the vote has lost its symbolic and practical value. The reality of cyclical electoral fraud and vote manipulation has transformed the democratic process into a mere ritual. The vote has ceased to be an instrument of citizen choice and has become a mechanism for legitimizing power and maintaining political elites. The absence of empathy manifests itself in political decisions that ignore the daily difficulties of Mozambican families. A state that punishes those who work and rewards those who govern poorly cannot claim moral legitimacy. This inversion of values has become the essence of the Mozambican crisis, a country where austerity has a face and a name: that of the ordinary citizen.

The discourse on “inclusive growth” sounds increasingly hypocritical in a country where the majority live on less than two dollars a day, while the political elite multiplies their income through subsidies, luxury cars, and official trips. When the government reduces the 13th-month salary of civil servants, freezes investment in essential public services, and at the same time maintains the high salaries of members of parliament, it clearly demonstrates a moral divorce between rulers and the ruled. The plight of Mozambican civil servants is that of a people who continue to serve the same people as always, in a cycle where those in power protect their own and poverty is treated as destiny. Thus, rights exist only on paper, and Mozambican workers will remain hostage to an economy of sacrifices and empty promises.

2025/12/3

Copyright Jornal Preto e Branco All rights reserved . 2025

Copyright Jornal Preto e Branco Todos Direitos Resevados . 2025

Website Feito Por Déleo Cambula