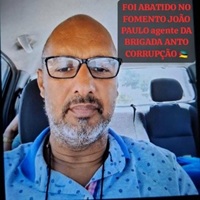

Fomento, SERNIC in mourning on the battlefield against corruption

Paulo Vilanculo"

The shootings have symbolically become a battlefield, where SERNIC and other criminal investigation forces seem to be waging an unequal war against increasingly audacious, organized, and infiltrated criminal networks. According to data collected by Integrity, the Fomento neighborhood, in the Municipality of Matola, Maputo Province, was once again the scene of death, in which a law enforcement agent, attached to the (DIO), who went by the name of João Paulo da Silva Gomes, known simply as João Paulo, was brutally shot and lost his life in circumstances that raise serious concerns about the state of extreme organized crime, exposing, once again, the growing insecurity experienced even by those who should guarantee it.

The term "SERNIC on the battlefield" comes to mind when it becomes known that the deceased had recently been appointed to the anti-corruption brigade, and this fact, far from being circumstantial, shifts common crime into the sensitive terrain of direct confrontation between the State and vested interests. This episode occurs in a context marked by repeated assassinations of law enforcement agents, some in the line of duty, others off-duty, but always in scenarios that point to a worrying pattern in which criminals no longer fear the State or the security forces, but, on the contrary, openly challenge them, displaying logistical capacity, weaponry, and strategic information. The fight against corruption in Mozambique has ceased to be merely an administrative or judicial exercise; it has become a high-risk arena, where investigating has come to mean exposing oneself to extreme retaliation. Investigating thus becomes an act of individual bravery, not of public policy, especially when the State does not guarantee operational security or secrecy, turning its personnel into easy targets. The assassinations of officials linked to the anti-corruption brigade seem to serve as an internal and external warning that investigating certain networks can cost lives. Thus, the "battlefield" extends into the very structures of the State, where silent battles are fought between legality and institutional capture, between justice and complicity, between investigation and cover-up.

Corruption is no longer just a target for SERNIC; paradoxically, it is also a test of its own integrity, resilience, and institutional survival. The fight against corruption, in this scenario, reveals itself not only as a public policy but as an institutional war. Therefore, an investigative body under constant attack loses moral authority, public trust, and operational capacity. SERNIC thus finds itself in an ambiguous and dangerous position: it is called upon to confront corruption, but simultaneously challenged to prove that it has not been, nor will it be, absorbed by it. This is put to the test not only by the scarcity of resources or logistical fragility, but by its capacity to maintain autonomy, loyalty to the public interest, and operational courage in a context where organized crime demonstrates a high degree of sophistication and impunity. As long as corruption is not treated as an existential threat and organized crime is not confronted as a parallel power, bullets will continue to be the final argument. These assassinations are not just more numbers in urban crime statistics; they represent a direct attack on the State, on the institutions of justice, and on the fragile efforts to moralize the public service in Mozambique. The execution of an agent linked to sensitive areas such as the fight against corruption raises disturbing suspicions about possible motivations for the crime, including retaliation, silencing, or institutional intimidation.

When an officer is killed, the message intended to be spread is not merely one of mourning; it is one of collective intimidation, directed at those who investigate and those who intend to investigate. Each murdered officer represents a dossier that does not advance, a network that is not dismantled, a process that dies before reaching the court. Each murder generates condolences, statements, and promises, but not profound structural reforms, not serious institutional cleansing, nor a real pact to protect criminal investigations. Selective homicide thus becomes a strategy for managing criminal risk: killing is cheaper and more effective than bribing when the investigator does not yield. The shootings are not accidental; they are the visible result of structural failures, political choices, and the normalization of impunity. The shooting takes refuge in chaos and establishes clandestine hierarchies. Where the law is weak, selective, or negotiable, violence emerges as the dominant language. The recurrence of these crimes without swift clarification and exemplary punishment sends a clear signal: killing an investigator pays off. Impunity becomes an incentive. The absence of credible internal investigations, accountability, and real protection for investigators creates an environment where brute force prevails over the law.

When criminal networks accumulate resources and privileged information, lethal violence becomes the quickest instrument to silence inconvenient investigations. As long as the perpetrators and, above all, the authors remain beyond the reach of justice, each fallen agent will not only be a victim of gunfire, but a symbol of a captured state, where fighting corruption is equivalent to entering a minefield alone. In a country where corruption is fought more in discourse than in practice, the physical elimination of a newly appointed member of the anti-corruption brigade sends a dangerous message that investigating can cost lives. In contexts of instability, selective violence, and diffuse fear, the public debate shifts from the demand for profound reforms to simple daily survival. The concept of "SERNIC on the battlefield" will thus cease to be a journalistic metaphor and become a literal description of a state that fights external enemies but resolves its internal fissures.

2025/12/3

Copyright Jornal Preto e Branco All rights reserved . 2025

Copyright Jornal Preto e Branco Todos Direitos Resevados . 2025

Website Feito Por Déleo Cambula